San Francisco Examiner September 25, 1991

Misery and hunger in land of plenty

Dwayne Hunn

“Buck sheis de do, shab? Khanna mangta hai. Boock laga hai…” he said, as he tugged my hand. He stood belt level and I turned away after glancing at him. He kept holding and tugging, as the teeming masses of Indians moved beside us on the sidewalk.

“Boock laga hai, boock laga hai, tora khanna mangta hai…” he said as he rubbed his stomach and tugged my hand. I tried to look at him as we kept walking in the crowd. In training they had told us that we would have to decide how to handle beggars. In training, they had told us that 1/2 of India’s beggars were purposefully maimed.

“How do they get a statistic like that, does the government go around and ask, `Did you purposefully maim your kid?'” I had skeptically asked.

During my first five minutes in the streets, I had trouble starring into the face of this boy whose cheek had a whole in it the size of a Kennedy silver dollar, ringed with pus, sores, exposed teeth and ugly gums. Ahead, curbside on the street, were skateboards that American kids careen around on for fun. In Bombay they are used by kids without hands, ankles or legs to reach the car or taxi at the light, grab its handle and beg, “Paise de do, shab… Gorib admi, shab..”

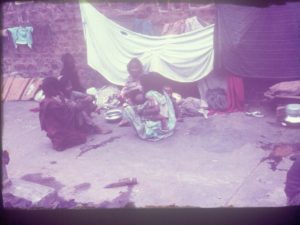

The homeless and poor seemed to be everywhere. In the financial district of the city, where piles of garbage were left to be picked up early in the morning, I naively asked the scavenger, searching the piles which the rats always worked, what he was doing. A weak “Khana (food), shab,” was his reply, as he continued slowly searching the mounds of garbage. On a train trip, I laid on my pack at a village station and watched a family with a pants-less child defecate diarrhea on the train platform, and use his fingers to lick it.

As a kid living on the poor side of Cleveland, I met only one beggar, whose cut foot my mother cleaned after she brought him into the house and fed him. As a Peace Corps volunteer, I saw them maimed and crippled and begging all day, everywhere.

Of course, I got to see the Taj Mahal, Ajanta and Allora Caves and stuff a kid from a working class family would not have had the vacation money to see. Those tourist sights made me develop a simplified philosophy of why the India I knew in the late-60’s had the human problems it had, and has. To build the palaces for the rich, and naturally cooled, hand carved caves for the influential religious classes took a tremendous number of manhours and resources. Energy that was not spent on irrigation systems, infrastructure and education.

Little did I realize how some of those experiences working on Urban Community Development in the slums of Bombay would prep me for today’s America. My first work site, the Worli Chawls slum had water available for only an hour a day, usually with enough pressure to reach the 2nd story of the typical four story tenements, from about 3:00 a.m. to 4:00 a.m. If you lived on the third or fourth story, you bucketed water up to store in your water drums.

For years now I have lived in affluent Marin County, California, where in recent years we were limited to 50 gallons of water per day per person. The I captured rain water in drums and saved shower water in buckets and bucketed it to some very basic toiletry needs. Homelessness and begging has become a growing problem in Marin and a bigger problem in Big Brotherly San Francisco.

On a shrinking planet whose resources are limited and whose population is pushing 5 billion with an increasing number of homeless and hungry, there is little justification in doing more Taj Mahals, even if we had powerful S&L financing and visionary Trumph leadership. There is obvious justification for increasing irrigation systems, infrastructure and education worldwide.

My two years of oversees work reinforced my belief that there is a tremendous need for expanding the Peace Corps overseas and its resultant educational benefits at home. Working on affordable housing and land use problems in the North Bay of San Francisco for almost 9 years continually exposed me to opponents of affordable housing, whose view of the world is dominated by preserving what they got and only allowing more palatial estates to be built. How their relatively powerful actions play on the stage the rest of the world must live on matters not. They fail to see how the use of our land to support and provide energy efficient transit modes and affordable ownership housing impacts not only those near their county borders but those oceans away in our shrinking and ecologically fragile planet. The NIMBYs (Not In My Backyard) elect NIMTOs (Not In My Term of Office) who usually produce LULUs (Less than Useful Land Uses) by doing DECME (Density Erasers Causing Million Dollar Estates) projects rather than meeting the working people’s and the environment’s housing, transit and community development needs.

The Maharajas’ produced Taj Mahals by edict. We do it through a more democratic process of meetings that produces a veiled but often similar result. To a Peace Corps volunteer who has seen and sensed what wasted hours and resources can do, it is hard to fathom why people would fight to add another 2% of Marin’s land to the 88% which is already in open space, agricultural preserve and parks; rather than support a rail oriented development that would provide affordable housing, child care and less car-dependent communities.

Failing to comprehend such logic, I often fall back to thoughts Kishore Thakar, an Indian friend, left me. Referring to his own caste-and-class riddled society he said, “People need to walk a mile in other peoples’ sandals to understand the toil and misery that goes into living the life of those who struggle. For those who move about easily, the blisters developed from that walk remove both the calloused perceptions some have of others and the scales that blind their view of what their actions do to others. It would do the world good if more people who move about easily served a few years doing what you Peace Corps are trying to do.

“Buddhists believe that each life should bring more enlightenment and less need for selfish desires. If in this life we do not become enlighten over what our actions cause to others, then our reincarnation should be to walk endless miles in the sandals of those upon whom our actions stepped most heavily.”

Dwayne Hunn is a Mill Valley free lance writer.